My book is finished

Here's what I've learned

Really? Tell me more!

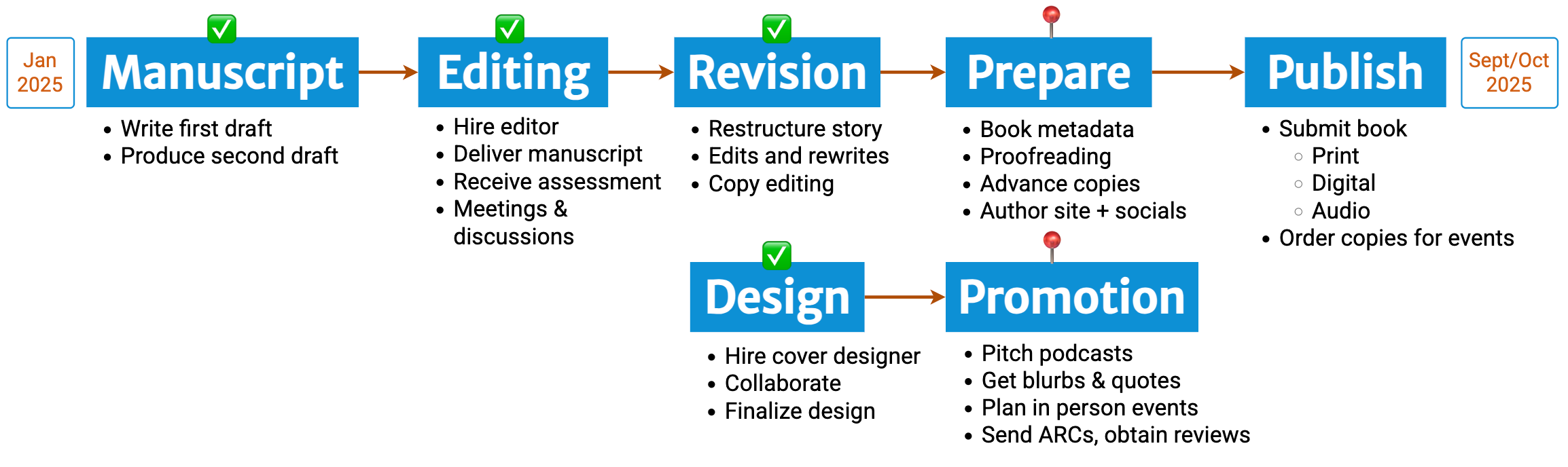

⬆️ Here’s a visual overview of the journey writing my first book, a memoir (Unflappable: Soaring Beyond a Diagnosis). I just finished revision and now I’m taking a breath before I dive into everything that needs to happen before the book becomes available for purchase.

I’m planning on doing special pre-order bundles, exclusively for Unflappable subscribers, so stay tuned for more details, and get subscribed if you aren’t already.

I am elated to share this book with all of you, your friends, neighbors, and people who see the cover and then are compelled to buy it. I’ve learned a great deal about myself and the mechanics of book writing and self-publishing since this year began; here are just a few things that come to mind.

Writing a memoir is more difficult than learning to fly

Let me add a disclaimer before I provide an explanation—learning to fly, as in the early training parts of becoming a pilot, in my experience, is easier than the sum total of effort needed to write a book. Maybe this is obvious, but both endeavors, at first, are primarily physical. In beginner training for flying, you learn how to move your body in concert with the wing and how to control it, building muscle memory, practicing the same movements over and over again. You become familiar with the sensations of being in the air, suspended, which your body wants to react against.

Similarly, the early stages of writing a book, getting from idea to manuscript, demand being in one place over and over again, training yourself to actually do the writing, sitting for hours, pen in hand, fingers to keys, and then making that a habit. Eventually, the effort needed to improve shifts, as motions become reflexive and natural—then it’s primarily a mental game. Same thing is true in paragliding, which is something I spend a fair amount of time unpacking in the book.

You need to have an editor

One of the reasons (beyond FAA regulations) we don’t fly in clouds is that you can lose all sense of awareness, unable to see and discern in the most important ways. This will probably happen if you decide to write a book and then manage to produce a manuscript—you will become so immersed in the process of creating the thing that you might forget you are writing it for a reader and you need to think about them. Or you may simply have no sense of whether you’re making progress, whether you’re producing something of value, giving the proper attention to the pieces of the story that are the most resonant, being mindful of place and structure, context and detail. I got lost in the clouds several times, but thankfully had an editor to help guide me back to blue skies.

I could (and may) write an entire essay on why working with an editor is a must-have if you want to produce a high-quality book length work. The parallel to flying is this: your editor is like your instructor, perhaps the most important choice you will make as you begin your journey.

Doing this well—self publishing—is expensive

Sure, you can cut corners, use AI, design your own cover, only publish e-books, but if you want a book that resembles titles that inspire you, this will require an investment, maybe a serious one. And maybe you won’t break even. I have no idea if I will and I approached the project with modest expectations. If I don’t break even, fine, I still wrote and published a book. If I do, wonderful, I can put that towards buying and writing more books.

I don’t like the phrase “vanity project” in the context of memoir, but it is important to be honest with yourself on motivations—why are you writing a book? I wanted to prove that I could, and decided that my story was worth sharing in book form. The end goal wasn’t to switch careers and become a full-time writer or instagram famous—neither of those things are likely to happen. So the investment, the money you’re willing to spend (and maybe not recoup) is in service of producing a work you’re proud of, a truthful reflection of who you are as a writer.

The other thing to point out is that no one works in and around the book writing world to get rich, which connects us back to paragliding. The vast majority of the people involved in the flying world live modestly, like editors and writers and bookish people in the world. If you have the means to go on a book writing adventure, spend the money and help support the people who do this for the love of the sport.

You should market your book (even if it’s painful)

In the story, I write about my aversion to the concept of selling yourself, building a personal brand, being LinkedIn famous—I don’t have the skills or the inclination. I’m not great in job interviews and I’m not someone who cares much about prestige and the traditional markers of success in the white collar world. So the whole idea of promoting my book, marketing it to an audience, writing bios and pitches, left me unsettled.

I really had to sit with this one for a while, but what I landed on was some version of

Suck it up, put some effort into this, just like you’ve been putting into writing the damn thing—you have to promote your book, come on now!

which then evolved into

Okay, yeah, I do know people in this community and that community and they seem excited about this project (yay!) and they want to help me (double yay!)

And then I just started making a plan, which usually means I’m on the right track.

Read some shitty books in your genre, it’ll boost your confidence

Before I finished my manuscript, I’d read at least a dozen best-in-class memoirs, books that inspired me, examples I could look at and aspire towards. Maybe I will be that sort of writer someday. I walked into the endeavor with a sense of what great looked like and developed a reference point, something to compare my output to. I think this is a helpful exercise, in moderation, establishing a baseline, seeing how other memoirists have told their stories, making note of what impresses you.

But then, alongside those books, it’s important to find some that just suck. I managed to find one flying-adjacent memoir in particular that was so bad, I felt compelled to write snarky comments in the margins, exclamatory statements, like I was talking back to the narrator, expressing my outrage and confusion over their choices. I began underlining every instance and form of the words “win” and “winning” and I stopped counting after about 50. I made it through more than half of this monstrosity of a book before I had to walk away, but I’m thankful I read it. Wow, my unrevised first draft manuscript is better than that slop, I thought. It’s a pleasant feeling to have, a welcome confidence booster during periods of self-doubt, when I wasn’t sure why I was even writing a book in the first place.

Odds are, you’ll want to write another

This is the writer’s form of If-you-give-a-mouse-a-cookie; if you manage to write one book, you know you’re capable of doing it, so why not the hell not? I have 2-3 concepts for future books floating around but I’m under no illusion that the next project will be easier. In fact, I don’t want it to be easier, I want to up the ante and take on a bigger challenge, something more expansive, collaborative in nature. And maybe I will pitch it, maybe I’ll write a query letter and a book proposal and the whole shebang. Who knows. But I do know, I’m going to write another book, because I know I can.

I also love Myles Werntz take on this topic ⬇️

What a journey and what perseverance!

Great news my friend. Can’t wait to get my copy.